Reading the dark wood: An analysis of “The Dark Would” art exhibition (2013)

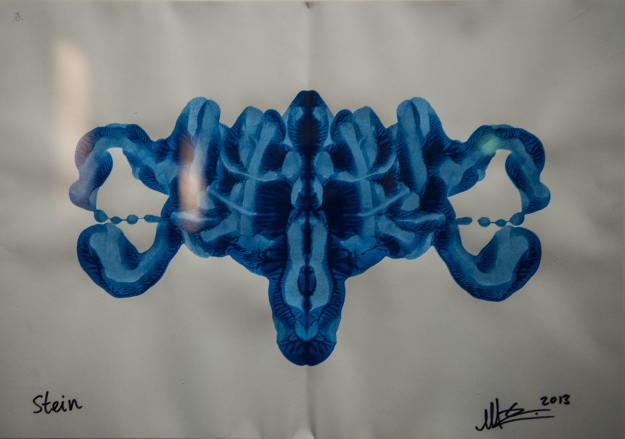

Essay by Ad Howells (2013).

The exhibition “The Dark Would”at Edinburgh’s Summerhall is an immersive installation focused on text based art; from poetry to painting with letters and typography, the exhibition examines and explores the “maze of living and dying”. Curated works from world-leading poets, including Jenny Holzer, Richard Long, Susan Hiller, Tom Phillips, Simon Patterson, Mike Chavez-Dawson, Tony Lopez, Richard Wentworth, Caroline Bergvall, Lawrence Weiner, Fiona Banner and many others, are included in the exhibition. “The Dark Would”, taking its inspired title from Dante’s Inferno, straddles the line between the immersion of the reading and theoretical engagement with text as a read medium, and an engagement with text from an aesthetic standpoint. Throughout the viewing of the exhibition, these twofold impressions are constantly shifted in a mobile audience engagement with the works, fluctuating between the text as a read device, and the typography and aesthetic reading of that text.

Curator Philip Davenport states : “This is an extraordinary gathering that asks what it is to have a body and to lose it. Perhaps this is best done by people for whom language is itself a state of in-between-ness… artists who use language and poets who are artists. Here, the material of language is a metaphor for human material, our own bodies. Whether poets, homeless people, outsiders, or art stars – we all have to find our way through the dark.'”

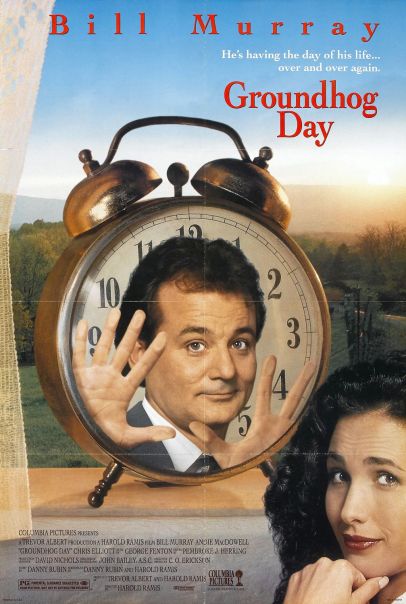

Figure 1. Dante’s Inferno.

The first exhibit you encounter in the exhibition is a old tome, the livery of its pages worn with time and its size larger than any average book you might come across in your daily activities, it is “Dante’s Inferno” and the pages lie open with the quote “In the middle of the journey of our life I found myself within a dark woods / where the straight way was lost.” On the page beside it an accompanying illustration picture, showing the figure of the central character stranded in a dark forest. As “The Dark Would” curator indicates, it is “Dante’s Inferno” that provides a theological nexus for the exhibition to rest. In Davenport’s introduction to the exhibition, there is a theologisation of language and the word, as a place, a locale to find oneself within. In the exhibition synopsis, Davenport states that “here, the material of language is a metaphor for human material, our own bodies.” It is this materiality, as well as immateriality of language that the exhibition constantly transfixes and transfuses; for Davenport states that “The Dark Would” is as much about “how we encounter our own mortality”, “it is about living in this moment, but living it knowing that we’re not always going to be here… it is the great thing, but also almost the great tragedy of humanity”.

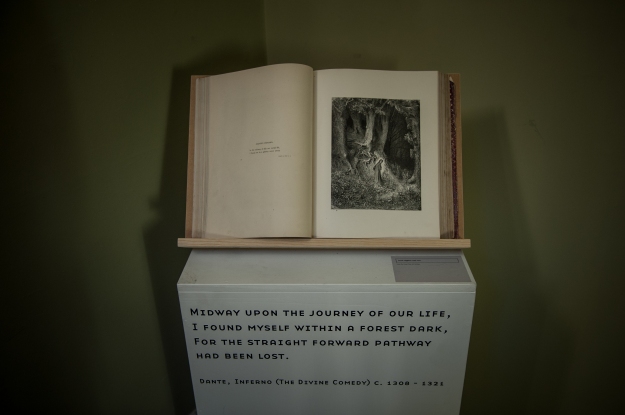

Figure 2. “The Dark Would, Nine Realms of Dead Poet, Version 1a 2013” by Mike Chavez-Dawson

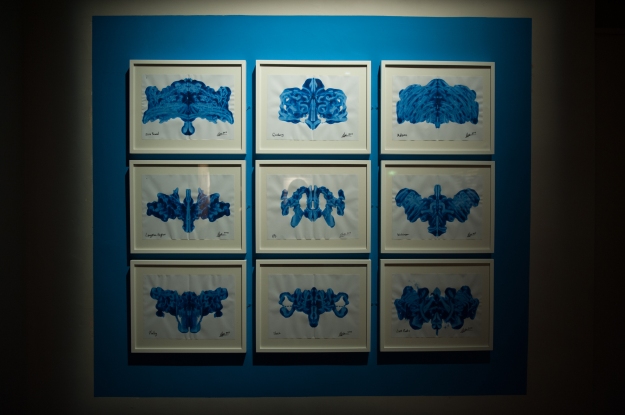

Figure 3. “The Dark Would, Nine Realms of Dead Poet, Version 1a 2013: Stein” by Mike Chavez-Dawson

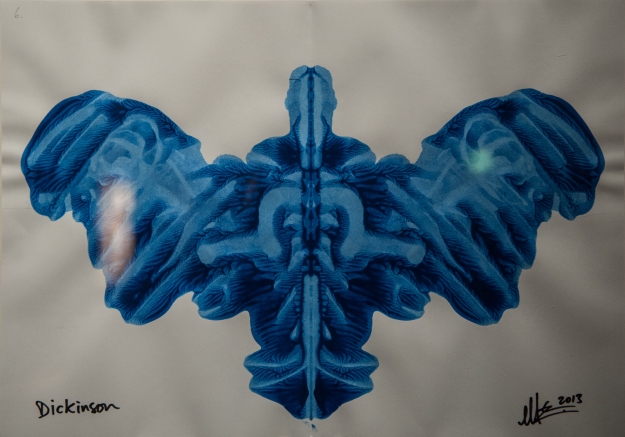

Figure 4. “The Dark Would, Nine Realms of Dead Poet, Version 1a 2013: Dickinson” by Mike Chavez-Dawson

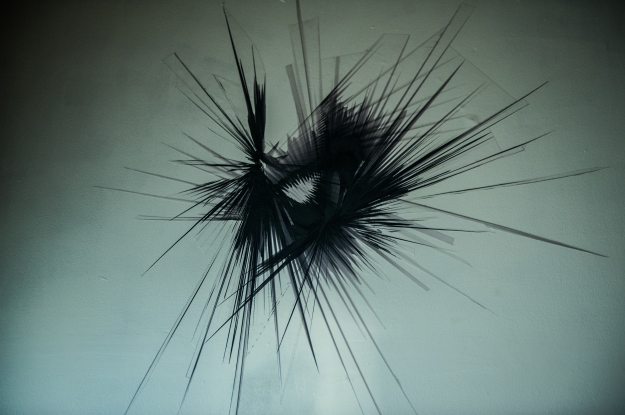

One exhibit namely “The Dark Would, Nine Realms of Dead Poet, Version 1a 2013” by Mike Chavez-Dawson, is a series of Rorschach abstract paintings constructed entirely from the names of dead poets, handwritten in wet blue paint, it appears like the cells of nuclei, or vessels of the human body, conjured from text form. The work inspired by Dante “teetering between comprehension and experience”, draws from “memories of the dead poets’ work”. It is the immateriality represented in the work, and the immateriality of the work itself, which once the show concludes will be burnt, before being remade again for another showing of the work, that engages with the theme of reincarnation and mortality. As the exhibition finds its central nexus in “Dante’s Inferno”, it talks personally about the middle-ness of a life, a state of “in-between-ness” as the synopsis states. Sufficiently as the wood, depicted by Dante where the protagonist finds himself and, “where the straight way was lost”, the forms in “Nine Realms of Dead Poet” are in a state of transformation upon the page, as state of forming, out of formlessness, or forming back to formlessness, like the early universe. The nuclei the artist conjures through paint are both saturated with the meaning of the dead, and also bereft of it, and this is a notion that the text from “Dante’s Inferno” engages with, the paradoxical state of “in-between-ness”, a no man’s lands of the soul. The metaphor for language as a human body, is explicitly demonstrated in this work, with the forms of names, becoming the forms of departed bodies, and departed language and words uttered in the written word.

It is the word, and the place of forming and formlessness that seems to ignite both the cognitive and material sensibilities that “The Dark Would” portrays. It is in fact this moment of creation that epitomises both the artist and the world as a synthesis between the hand and the act of creation. John the 1st the Bible immediately comes to mind. “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.” (The Bible, NIV, John 1) “The Word became flesh and made his dwelling among us. We have seen his glory, the glory of the one and only Son, who came from the Father, full of grace and truth.”

The words in “The Dark Would” are both fleshly and spiritual, as they depict, as Davenport suggests what is perhaps the great tragedy of the human condition, the cognitive awareness that “you will not always be here”.

Figure 5. “The Secret” (2004) by Marton Koppany.

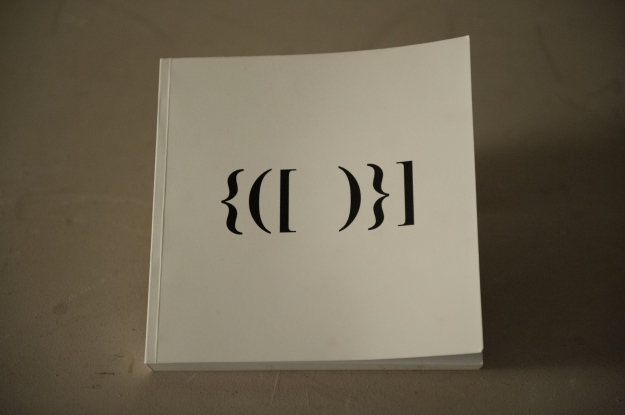

As you will reluctantly leave behind the great tome of “Dante’s Inferno” you then ascend the stairs and you will come across two giant sets of gaping parentheses, brackets leaving the gap for nothing between them save for a doorway, upon which you reside (“The Secret”). The first room you come upon featuring a site based poem installation piece by Stephen Emmerson entitled “Albion”, is as much about engagement with that beyond the living as many of the other works in “The Dark Would”. Assembled from a sheet of plastic cloth, with four typewriters at each corner, and a pentagram at its centre, Emmerson’s “Albion”, invites viewer participation to engage with the work of William Blake, “the visionary English poet and artist”. “Participants can channel Blake, using the pentagram and typewriters.” During my visit to the exhibition I saw a few people tapping away fervently trying to construct their own poetic work to mirror the exhibits desire.

Figure 6. “Albion” by Stephen Emmerson

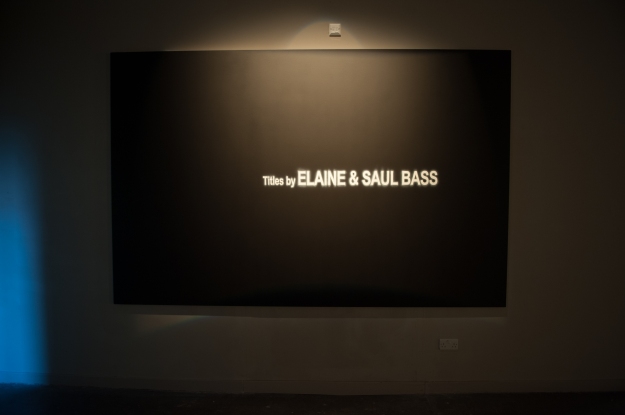

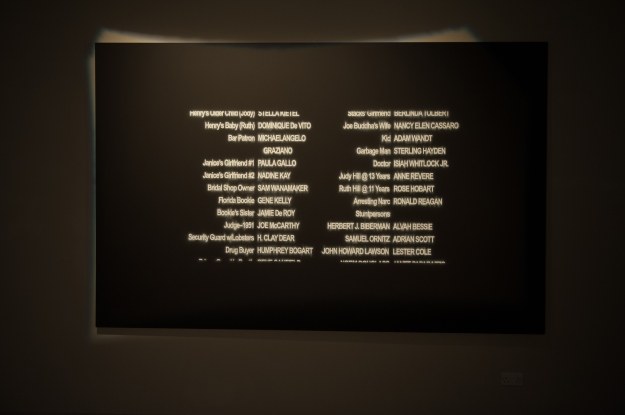

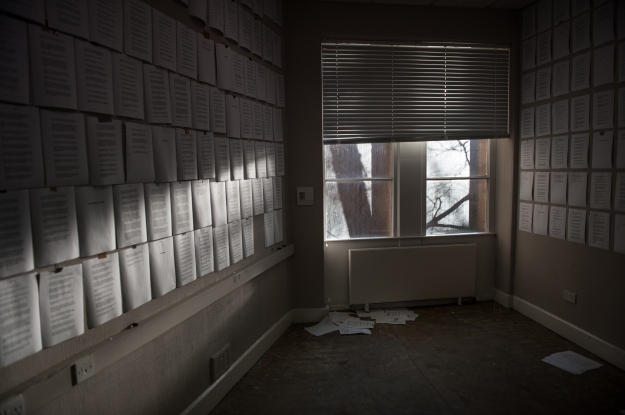

Upon entering a large hallway room, that is at the top level on the Upper Church Gallery of Summerhall, a room filled with art and lofty beams hung across the ceiling, you see works from Simon Patterson in “Black-List: Henry’s Older Child, Black-List Elaine & Saul Bass, 2006”. “Blacklist” (2006) as exhibited here, consists of two large scale canvas works from Patterson, which is part of a series of 10 paintings, in the “Blacklist” series, the paintings depict scrolling semi-fictitious title credits for films painted on black, emulating the theatrical cinema screen. The names of screenwriters, directors, cinematographers, actors and cast and crew are depicted, and Patterson’s anamorphosis and combination of multiple film titles enables him to create his own unique credits. The credit paintings in “Blacklist” are in part a commentary on the paratexts surrounding the work of film or art, and in the short accompanying book for “Blacklist”, contains an essay examining these associations, of the paratextual work that surrounds the main predominant work of art.

Figure 7. Simon Patterson “Black-List

Figure 8. Simon Patterson “Black-List

The notion of the paratext is later examined in a work “Holocaust Museum” (2011) by Robert Fritterman that reframes captions of holocaust photographs from the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, DC. The textual work in captions once again re-imagines in this case pictorial rather than motion picture work, through textual means, thus providing the audience’s imagination a place to fill in the visual images in their mind’s eye, as well as commenting on the nature re-contextualised image as a translation from the spectatorial pictorial dimension, to the text based imaginative realm. The work reminded me of references for a dissertation or essay work, and the seemingly autocratic system of categorisation juxtaposed with the emotions of the content.

Figure 9. “Holocaust Museum” (2011) by Robert Fritterman

Figure 10. “The Secret” (2004) by Marton Koppany.

On the wall of the room is a print of the parentheses work “The Secret” mentioned previously. All encompassing these three mirrored sets of brackets leave the opening and room for a place of philosophical and existential questioning, in a sense that is what “Dante’s Inferno” verse alludes to, the notion of finding yourself in a dark wood. Here, perhaps the parentheses describe something of a forest, where the gaping void between them, serves as the human place of interior and physical geographical respite, as if the human rests, inclined among the typography itself. Brackets become trees, typographical symbols surrounding our former use, entrapping us in the dark wood, upon which we are left to make our own content for the vessel of the parentheses to hold. “The Secret is wordless, and in a sense imageless… The absence of other text or symbols means the brackets could be linguistic or mathematical, though their order doesn’t conform to the normal hierarchy of either content.” “The Secret” conceives a “dialogue between presence and absence”, “a dialogue between “poetry (textual, visual or concrete) and visual art”, between “space and mark” and between “present and possible futures.” (Matt Dalby, April 28th 2013). The positioning of the parentheses at the entrance to the Upper Gallery of the exhibition configures that passage and the exhibition as a place for philosophical questioning, as if the Summerhall exhibition is its self, a dark wood, or a dark “would” a possibility upon which to conceive, and imagine possible futures through re-contextualisation, and the gaping hole between the brackets is therefore a metaphorical passage for the questioning to take place. The parentheses presence at the opening of the exhibition hall is as much trapping as liberating, with it signifying and emotional and architectural trapping, as if the artists of the exhibition are imprisoning the viewers in their wood, their lair of questioning.

Figure 11. “A quilt for when you are homeless” (Arthur + Martha, 2012). By homeless people in Manchester in collaboration with arts organisation “arthur + martha”.

In the centre of the exhibition floor is a handmade quilt work stitched by homeless people in Manchester, a work created in collaboration with arts organisation “arthur + martha”, the quilt carries the words and thoughts of the homeless sown into its cloth. The work brings together different groups of people, and states of living, offering the viewer a place for recapitulation upon their own place and relation to these people, as well as providing a “keepsake, an offering” for when the writer and reader encounters emotional difficulty.

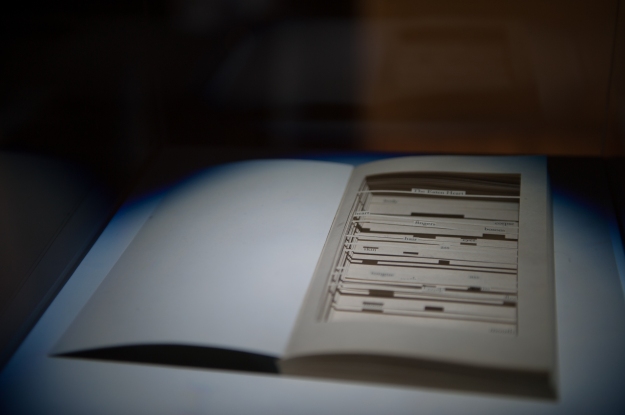

Figure 12. “Imprisoned” book. By Richard Wentworth.

Figure 13. “Imprisoned” book. By Richard Wentworth.

As you approach the far walls of the long Upper Church Gallery you will encounter a number of works by Richard Wentworth, that explore the trappings of the word. As we have previously established it is “The Dark Would” exhibition’s use of “the material of language” as a “metaphor for human material, our own bodies”, that epitomises the trajectory of the works shown here, and “Plume”, (2011) and “Said the Spider to the Fly” (2013) works consisting of caged books explicitly display this metaphorical analogy. “Wentworth has made numerous works where dictionaries are forced to house ‘bookmarks’, which resolutely refuse to fit. As if this mixture of childlike joy and adult rage were not enough he has know started to ‘imprison’ books.” Wentworth’s imprisoned books, capture the spirit of the enclosed and the world beyond, they are configured as “lockable architectures”, and the visual concept of the cage draws attention to the dichotomy between the books outer exterior, the “face” and “visage” of its covers, and its interior organs, its pages. The book therefore becomes “an idea” a “concept” to be thought about, rather than an entity to be understood and apprehended. “These flexible wire enclosures enhance the book as an idea”, while its soul is lost and instead re-imagined and reconstituted in the eyes of the beholder. Wentworth thus re-contextualises the book as a desired and admired object, curiously through its entrapment, it is perhaps this that most fundamentally captures the relationship between the word and the body. The trapped book is idealised, and longed for, because it cannot be read, the form of the book betrays the forming or formless identity within its pages. It is as if the book itself was an idealised lover, waiting enigmatically yet unattainable, this lover and this object of desire is perhaps desired only because it cannot be entirely known, it cannot be touched, caressed or read through love – instead love is projected upon it, and dreams and desires are found in the mind’s eye of the beholder of the desired lover. Therefore, Richard Wentworth’s trapped book works provoke a dialogue between the identity of the spectator and the spectated, the lover and the loved who cannot meet, but can only meet in the ephemeral instance of a gaze. Instead the lover and the loved are consoled through envisionment and imagination of the other, and perhaps this is ultimately what Davenport’s “The Dark Would” strives to capture and instil; namely the relation between confounded words and images of words, that seem to be speaking a complex and sometimes paradoxical language. To the extent that “the material of language is a metaphor for human material, our own bodies”, Wentworth’s trapped book assimilates a metaphorical dialogue with the conversations of human actuality. The desired body of the book, and the desiring body of the lover enact the body language of looks and glances of attraction, it is the dichotomy between this oftentimes deceptive body language and the interior world of the intellect that transpires this conversation, between aesthetic and interior meaning, provoking lies, truths and the visions that they capture. The body language metaphor for the trapped book stratifies the ideal of this emergent desire to capture language both pictorially and intellectually, and it also suggests a very physical relationship that is thematic throughout this exhibition, this sensory physical relationship is also captured expressively by Richard Long’s textual walk art pieces.

As the book of “Dante’s Inferno” lies open and vulnerable, to the eyes of the observer, as if displaying all of its internal organs as pages for us to see, it is Wentworth’s trapped book that coheres with this act of seeing, and this act of apprehending that the exhibition first drew us into; and it is certainly the act of contemplation of the reemergence of the self, and desires for the future that the “dark wood” (“In the middle of the journey of our life I found myself within a dark woods / where the straight way was lost.”) seeks to illuminate. We as viewers are both the prey and the predator, we enact looking like hunting and being addressed with the vision of art as being hunted.

Figure 14. “Chasm of Lethe” (2012) by Eric Zboya.

At one side of the hall your eyes will drift across a work by Eric Zboya entitled the “Chasm of Lethe” (2012), the work is an abstract and exploded form, in a virtual sculpture of two dimensions, the work takes the text from Dante and reconfigures it in sculptural form. The work displays a transfusion of text and the visual, to the extent that the visual has become the text and the text has become the visual. The manifest intimacy between textual and visual forms is so intense that the two mediums have wholly become each other, and it is as if they have given birth to an offspring that shares their traits and genetics, this is perhaps evident in the lines and letter like resembling forms that Zboya’s “Chasm of Lethe” is constructed from.

Figure 15. “ONE HOUR SIXTY MINUTE WALK ON DARTMOOR, 1984” by Richard Long.

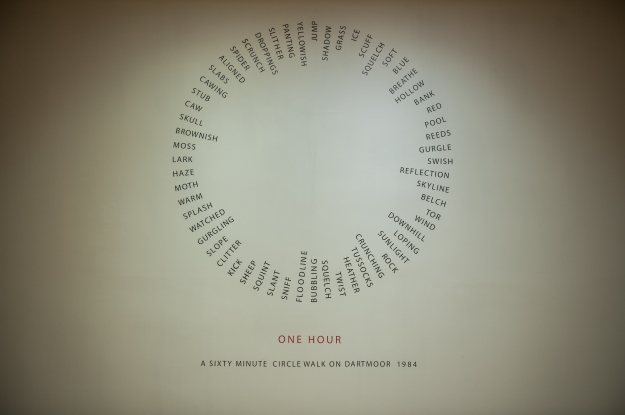

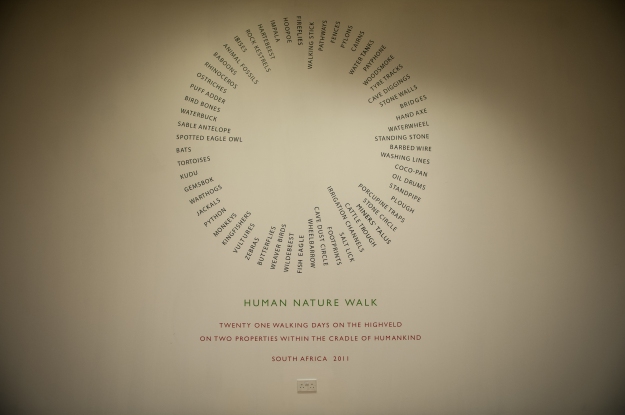

In the Lower Gallery of Summerhall are two large works from Richard Long, separated by 60 years the works are formed as huge circles of descriptive words, desiring two walks, a “ONE HOUR SIXTY MINUTE WALK ON DARTMOOR, 1984” and “HUMAN NATURE WALK, TWENTY ONE WALKING DAYS ON THE HIGHVELD ON TWO PROPERTIES WITHIN THE CRADLE OF HUMANKIND, SOUTH AFRICA 2011.” The circular works evoke images of the texture and sensory aspects of walking, providing a circular immersive impression of the act of walking as an engagement with the senses of the activities of nature, the birds, the trees, and the ground beneath the feet. Long’s works attribute to the sensory aspects of living and the motion of walking, in hearing, feeling, sensing, touching, looking and apprehending the world around us. As we have seen through analysis of previous works, such as “Holocaust Museum” for example, it is the images that the text conjures that is part of the illusion that text art offers, and Long’s circular text art certainly reconfigures some of that kinetic energy of walking and motion, both in the rhythm of the words when they are read, and in the visual display of the words, in their circular form which provides them with energy. Long’s words, both speak to something of the human body as a locale for words, and also the physical sensibilities of the human body in the world as it engages in physical heat, exhaustion and splendour with the tactile real world of South Africa. As the synopsis of the exhibition suggests that “the material of language is a metaphor for human material, our own bodies.” Long’s text art can be seen to epitomise this. Like the “bodies” of the dead poets in “Nine Realms of Dead Poet”, Long evokes the nature of being alive, and the awareness that you are alive, tingling with the senses of actuality, as you pass through the world on the kinetic and mobilising journey of taking a walk.

Figure 16. “HUMAN NATURE WALK, TWENTY ONE WALKING DAYS ON THE HIGHVELD ON TWO PROPERTIES WITHIN THE CRADLE OF HUMANKIND, SOUTH AFRICA 2011.” By Richard Long.

In the “The Dark Would” volume 2, Carol Watts eloquently describes such a process that Long’s works manifest, “What might it mean to walk with Richard Long? I am thinking here of walking as a transposition in the carrying of through of thought. A spatial poesis for limbs. Along and between an assembling of forms, from the unwitnessed event of a making in the natural environment, to its visual registries as photograph, text and sculpture.” The assembling of the medium of the world, as registered through senses, is conceived in the act of walking and as “Nine Realms of Dead Poet” suggests, it is this forming of forms, and breakage of formlessness, back to formlessness as a reincarnation process, that the circle offers us; for the circle is a re-incarnatory medium for visual display, as its reading forms a process of a never ending return to starting again at the beginning. As bodies walk through time, confronting both themselves in others and in nature, so do bodies walk through a sea of words, as evoked in the numerous text-art found in this exhibition, and the circular pieces mobilise the viewers’ eye as it traverses across their words, taking the eye for a walk.

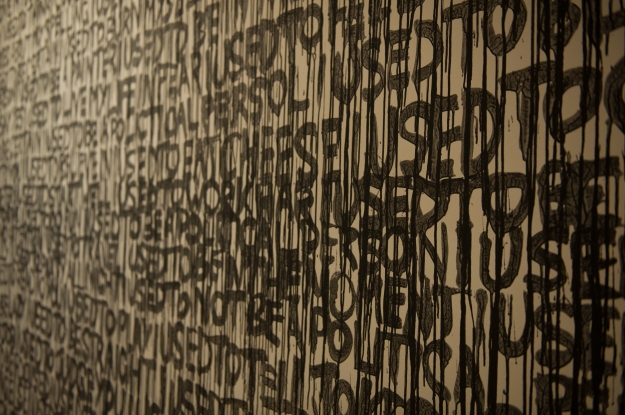

Figure 17. “I used To” (2013) By Sarah Sanders.

In the hallway at the centre of the Lower Galleries you will come across a large text art work by Sarah Sanders, “I used To” (2013), the work consists of sentences beginning with “I used to…” and then following with a statement such as, “I used to be ashamed”, being and example the artist provides in a video for the Internet channel Summerhall TV (2013), these seemingly personal statements are emblazoned upon the wall, in black paint, their barely legible dripping letters running tears of paint down the wall surface. Sander’s work epitomises something of the impossibilities and possibilities of language both as a executory and a recreational medium. Sander’s use of “I used to” configures an element of time and identity, as she looks back at a past self or identity of her artistic self. Once again mobilising the theme of “Dante’s Inferno”, the work “I used To” is a place for interior recapitulation and reflection. Sander’s words become vehicles to mobilise temporal looking as well as aesthetic surface looking, and the visage or face of the words themselves clearly attribute to that ideal; their dripping quality signifying something of the untamed nature of the soul, that does not want to admit its suffering, its woes or its misdemeanours.

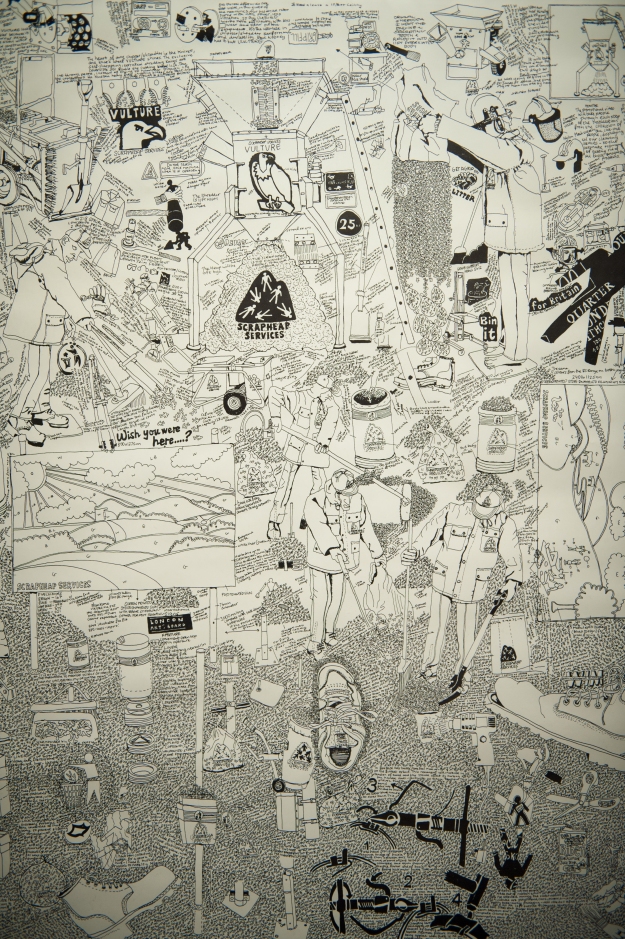

Figure 18. “Scrapheap Services” (1996) by Mike Landy.

As much as literature and language are fundamental aspects of human culture, and we have seen the displayed synthesis and disparities between what is said through language and through the facade or aesthetics of language, two artworks explicitly display these ideals. One by Mike Landy in “Scrapheap Services” (1996), and the other a poster graphic design comic strip by Revue Litteraire Letteriste for Directeur Alain Satie. Landy’s “Scrapheap Services” poster fantastically depicts various emblems of British culture and nature and even humans being swept or conferred into trash mounds. The work depicts workers sweeping letters and miniature human bodies into trash heaps and trash bags. “Scrapheap Services” suggests both the potency of language as a very physical, affective material and fabric of society, and the intimate relation between humans and words, suggests profoundly by words and humans sharing garbage heaps and being disposed of as seemingly equal entities.

The Revue Litteraire Letteriste comic strip is adorned with letters, that seem to transfuse and mitigate with the identity of the protagonists, displaying language as an affective sexual, communicative, and intellectual ideal that actually becomes part of the anatomy of characters’ faces and visages.

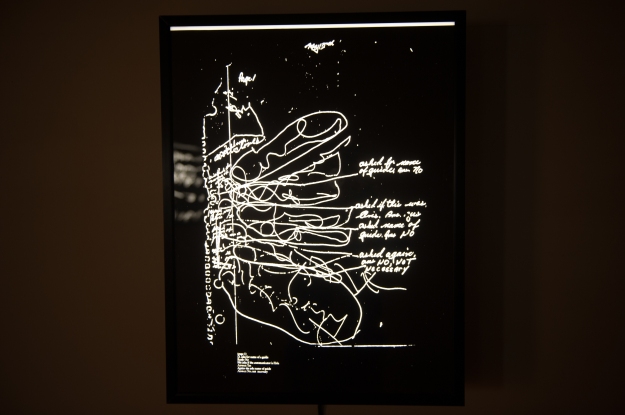

Figure 19. Susan Hiller’s “From India to the Planet Mars, 1997-2004.”

The significance of the aesthetic facade of letters is continued in the work of Susan Hiller’s “From India to the Planet Mars, 1997-2004.” The work consists of twelve text art drawings made upon black, with illuminated light-boxes that catch the white highlights; the work displays some of the relationships between writing and drawing, her works are automatic, and capture the effervescence of the two mediums where letters turn into drawings and drawings into letters. To return to the relation between the purely aesthetic and the aesthetic meaning that lies beneath the facade of these artworks, Hiller’s work reminds us of the nature and proximity of meaning and form, where typography, drawing and meaning seem fundamentally interlinked. As in the previous example of Sanders, “I used To”, the artist uses words and images interchangeable to evoke and capture ideals and emotions. Moreover, Hiller’s work captures something of relationships between people, as well as depicting images alluding to the greater universe and the cosmos.

Figure 20. Jenny Holzer’s “Lustmond”, (1999)

No other work than Jenny Holzer’s “Lustmond”, (1999) in the exhibition epitomises more explicitly that dichotomy between the beauty of form and aesthetics and the horror of meaning and content. The tiny LED display work from 1999 is a small screen with scrolling and mesmerising lettering that flashes in multiple colours and provides a seductive immersive rhythm, yet upon closer inspection the text’s content is a response to violence against women in war. The significance of Holzer’s image work lies in its ability to confront and transform viewers expectations and preconceived notions surrounding beauty and brutality. While the scrolling texts offers a mesmerising visual sanctuary for the ocular organs, it shatters the seductive framework of this aesthetic beauty, with the savagery of content, and the actual reading and apprehension of language. Thus Holzer counters the brutal message of language with an aesthetic facade of visual language, that betrays its wanton form. With allusions to the title of Marton Koppany’s parenthesis work “The Secret”, Holzer’s light display, holds its secret within the ever evolving boundaries of form and content.

Figure 21. Book of Stephane Mallarme (Heart Fine Art archive, 1842-1898) poems.

You will turn to your right and out of the corner of your eye entrap a curious object in your gaze. Sitting beside Jenny Holzer’s “Lustmond” and dominating the room in this Summerhall exhibition, is a book of Stephane Mallarme (Heart Fine Art archive, 1842-1898) poems kept in a cage, the poems were some of the first to pioneer a visual approach to the layout of a poem on the page, where liberated words would form positioning without the spatial constraints of traditional verse layout. Like Richard Wentworth’s “Plume”, (2011) and “Said the Spider to the Fly”, (2013) the caged book communicates notions of the written language the liberation and entrapment that it provides us with. The free flowing spatial cartography of Mallarme’s poems, represent the ability for poems and literature to take us into a liberated world of our mind, while the surrounding cage represents the physical world of our reality which is sometimes guarded from our dreams.

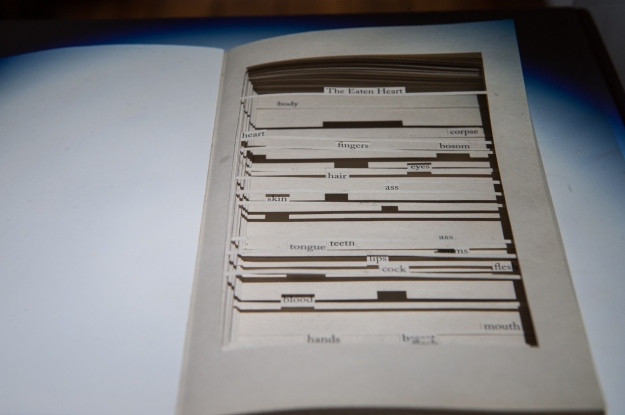

Figure 22. “The Eaten Heart” (2013) by Carolyn Thompson.

Figure 23. “The Eaten Heart” (2013) by Carolyn Thompson.

In a small darkened room you will wander through a collection of figurative exhibits, predominately mannequins wearing T-shirts displaying philosophical slogans, and a small exhibit will catch you attention. Barely recognisable at first, this exhibit does not immediately stand out. However, upon closer inspection you realise that “The Eaten Heart” (2013) by Carolyn Thompson directly confronts and epitomises the central central themes of “The Dark Would”. Consisting of a small softback Penguin book whose pages and words have been removed “with the use of a scalpel” , the book is left interred in a skeletal form, that leaves only words that “pertain to body parts”. The book “The Eaten Heart” is in itself the artists’ adaptation of Penguin Great Loves version of Giovanni Boccacio’s “The Eaten Heart: Unlikely Tales of Love.” As the synopsis suggests, it is “By removing these words from their (former) context and grouping them together, (that) their significance changes dramatically, celebrating the abundant innuendo in Boccacio’s original text.” What “The Eaten Heart” captures is the notion of the exhibition’s central metaphor, that of the words on a page and the anatomy of the book resembling the human body. Thompson strips away the primary flesh of the text, so that all that remains is the consistent skeleton, perhaps suggesting and questioning the nature of the skeleton as being what we are remembered for. The words in themselves conjuring aspects of human anatomy, body, heart, fingers, bosom, corpse, eyes, hair, ass, skin, teeth, tongue, lips, cock, flesh, blood, hands, mouth, save to stratify that despite the entity of the human body being a vehicle for thought, this is what it has ultimately been deprived of through death. No longer a cognitive thinking being the skeletal body, consists of pure remains, or the remains of thought, like the remains of thought evident in this book, and the gaping holes for its lost mourned for text. It is interesting to note that while many of the parts of the human body, are those that would be lost in skeletal remains (hair, flesh, heart, blood), themselves evident viscera organs and liquids that exist only in the alive body, it is also the absence of the thinking cognitive organs such as the brain, the rational organs that we use to comprehend that we are alive, that epitomises the betrayal of the thinking, cognitive human. Despite the heart connotations prevalent here. If the “Eaten Heart” is both a twofold eulogy to the mortality of language and ourselves, it is also an emblem of the demise of meaning, when the soul is lost. Dante’s Inferno, “In the middle of this our mortal life, / I found me in a gloomy wood, astray” seeks to comprehend and discover the identity of the human spirit, and perhaps this is the miscarriage of walking lost into the darkened forest, the fundamental stripping away of organs, of the heart and the flesh among them, as a revival to the absolute nature of the human condition and what is means to be alive, and to enact living upon all things.

When you emerge from the dark wood, perhaps you will breathe more slowly as you have traversed that midway period of contemplation, and have learnt many things about yourself along the journey. Only, it is now time to find the way you were searching for.

Reading the dark wood: An analysis of “The Dark Would” art exhibition (2013)

Essay and accompanying illustrative images by Ad Howells, 2013.

“The Dark Would” runs from Sat 07 Dec 2013 to Fri 24 Jan 2014 at Summerhall, Edinburgh, Scotland, United Kingdom.

Full details and video about the exhibition are available from the Summerhall website at www.summerhall.co.uk.